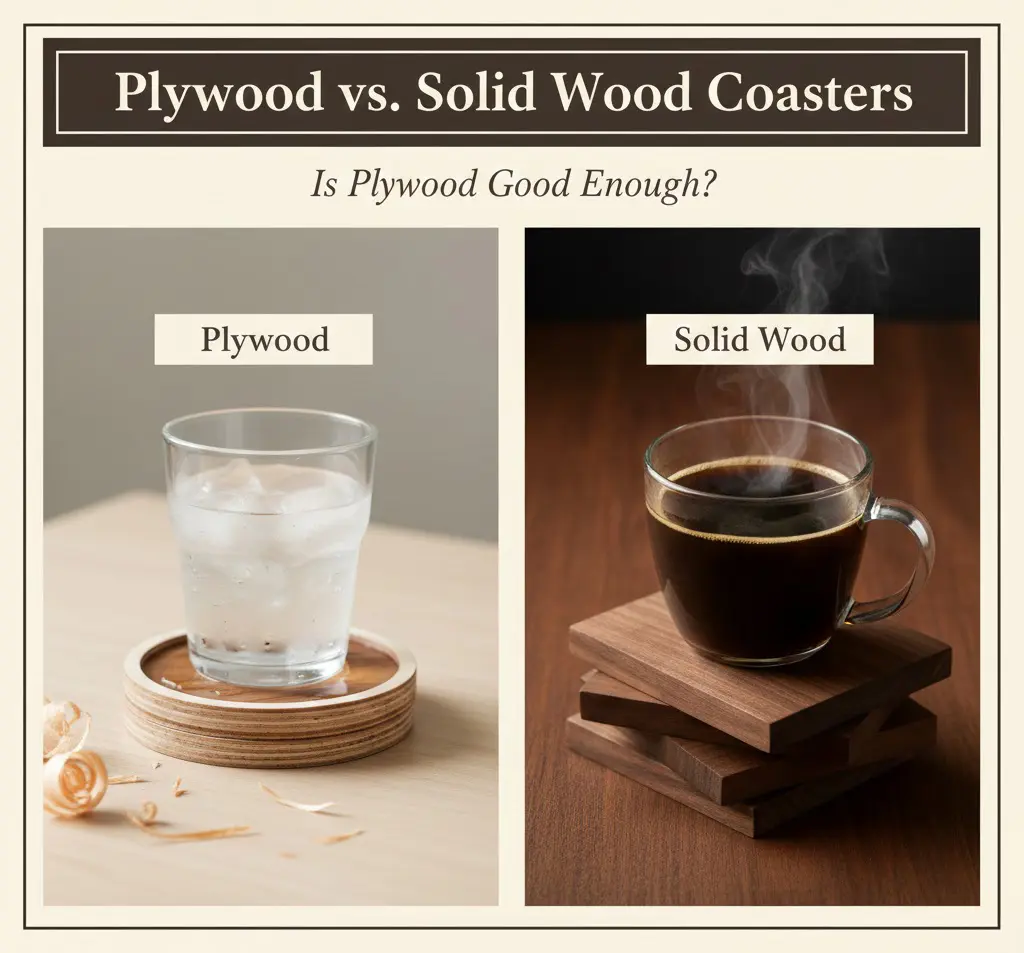

Buyers comparing materials for coasters often face a dilemma: plywood seems affordable but carries a reputation for being second‑best to solid wood. In manufacturing terms, that perception can be misleading. Plywood’s 90‑degree cross‑grain layers deliver balanced strength and moisture resistance, often outperforming single‑grain solid wood boards that can warp with humidity. Premium plywood panels also meet strength ratings around 4.41–6.28 GPa in Modulus of Elasticity and 21.80–34.70 MPa in Modulus of Rupture, putting them closer to solid hardwoods than many expect.

This article breaks down plywood vs. solid wood with data on structural stability, warping behavior, and cost efficiency. You’ll find side‑by‑side comparisons of mechanical properties, waste percentages, and finishing performance—so you can decide whether plywood is strong enough, consistent enough, and cost‑effective enough to meet your production and design goals.

The Plywood Stigma vs. Reality

Plywood is often seen as a low-cost substitute for solid wood, yet its layered 90° cross-grain structure delivers impressive strength, stability, and moisture resistance, making it a practical and sustainable alternative in modern woodworking and design.

Why Plywood Gets a Bad Reputation

Many people see plywood as cheap or artificial because its layered edges and adhesive bonding differ from the natural appearance of solid wood. This perception links it with lower-end or temporary furniture.

Its reputation also comes from misunderstanding its durability. Some assume plywood warps easily or loses strength over time, which is not true for higher-grade panels.

Traditionally, solid wood has been favored for its visible grain and craftsmanship, giving it a sense of prestige and individuality that plywood, as a manufactured product, often lacks in perception.

Because plywood is made from bonded veneers, its engineered structure is sometimes mistaken as less “authentic,” even when it performs better mechanically in many applications.

The Engineering Behind Plywood’s Real Strength

Plywood gains its structural stability from veneers laid at 90-degree angles to each other. This cross-layering balances strength in both directions, minimizes splitting, and reduces the effects of humidity changes that often distort solid wood boards.

A-grade veneers feature clean, defect-free surfaces suitable for visible finishes, while lower grades like X-grade may contain knots or patches. Marine-grade varieties use water-resistant adhesives and dense cores that perform well in damp spaces, from bathrooms to boat interiors.

The bonding adhesives between layers often exceed the veneers themselves in bending and humidity resistance. This means a sheet of quality plywood can handle static loads and moisture exposure better than equivalent solid timber widths in many construction or furniture situations.

Research consistently shows that although solid hardwoods like teak or sheesham still lead in raw density and load-bearing across long spans, high-grade plywood meets or surpasses solid wood in dimensional stability and durability where environmental changes matter most. Its efficiency and sustainability make it a reliable option for builders and designers balancing performance with cost and resource responsibility.

Solid Wood: The Beauty and the Warping Risks

Solid wood delivers rich grain variation and natural beauty but can warp when humidity shifts cause uneven shrinkage across the grain. Dimensional limits and proper moisture control are essential for stability.

Natural Appeal and Structural Behavior of Solid Wood

Solid wood panels display unique grain variation, color tone, and depth that come from the tree’s growth rings and species. Each piece reflects natural patterns, making every panel distinct even within the same species batch.

Because wood is anisotropic, it reacts differently along its radial and tangential directions. This means dimensional movement occurs unevenly as humidity changes, with more expansion and contraction across the grain than along it. These internal stresses are what make solid wood responsive to environmental conditions.

Woodworkers continue to value solid wood for its authentic texture and tactile warmth. Despite its natural movement tendencies, its depth and aesthetic merit make it a preferred choice for high-end projects where genuine material character matters.

Moisture, Dimensional Limits, and Warp Tolerances

Warp describes the deviation from original flatness caused by uneven moisture content across the panel thickness. To keep panels stable, manufacturing targets an equilibrium moisture range between 6% and 9%, ensuring dimensional balance during fabrication and lamination.

Tangential shrinkage can reach nearly twice the amount of radial shrinkage. When this difference goes unbalanced, solid wood may develop bow, twist, or cup. These deformations directly relate to grain orientation, exposure, and changes in relative humidity during storage or installation.

Manufacturing tolerances also apply, typically within ±1/32″ (±0.8 mm). When panel dimensions stay inside these limits and environmental humidity is controlled, solid wood maintains reliable geometric integrity. Beyond these boundaries, structural stress can accumulate, leading to visible curvature or joint separation over time.

Research into wood behavior highlights that tangential-to-radial shrinkage ratios near 2:1 are primary drivers of warping in large-format panels. Engineered materials like plywood reduce this effect through cross-grained construction that balances moisture stress along multiple directions. While solid wood wins on appearance and authenticity, its stability depends on precise fabrication conditions and consistent humidity control within 6–9% equilibrium moisture content.

Plywood: Engineered Stability and Strength

Plywood’s layered design gives it high strength and dimensional stability. By cross-laminating veneers at right angles, it resists warping and splitting while maintaining predictable stiffness and load-bearing performance verified through recognized strength standards.

| Key Data | Measured Values | Standards / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Modulus of Elasticity (MOE), Modulus of Rupture (MOR) | 4.41–6.28 GPa MOE; 21.80–34.70 MPa MOR (specific gravity 0.4–0.6) | ASTM D1037, ASTM D3043, PS 2‑04, EN 636 |

How Cross-Laminated Layers Create Stability

Veneers are arranged with alternating grain directions to limit expansion and shrinkage across the panel. Each layer acts to counter the movements of the one adjacent to it, spreading stress evenly and minimizing deformation when temperature or humidity fluctuates.

This cross-grain structure provides isotropic strength characteristics across the plane of the sheet. It prevents warping and surface checking common in solid lumber, helping plywood retain its intended dimensions and planar stability when used in structural applications such as flooring, sheathing, and cabinetry.

Measured Strength and Certified Performance Standards

Plywood is tested through standardized mechanical evaluations. Its typical Modulus of Elasticity (MOE) ranges from 4.41 to 6.28 GPa, and Modulus of Rupture (MOR) from 21.80 to 34.70 MPa for densities in the 0.4–0.6 specific gravity range. These values show reliable stiffness and bending capacity for structural design use.

Performance validation comes through recognized testing protocols including ASTM D1037 for panel strength, ASTM D3043 for construction-grade panels, PS 2‑04 for U.S. performance ratings, and EN 636 for European classification. Certification entities such as the APA issue graded plywood labels (A‑C, B‑B, CD Structural) to identify allowable shear modulus, exposure category, and bonding durability suited for interior or exterior assemblies.

Research Summary

Laboratory data show plywood’s structural behavior depends on balanced veneer layering, where outer face plies carry most of the bending load and core veneers manage shear. With cross-laminated construction, plywood exhibits consistent MOE and MOR levels comparable to high‑quality solid wood, yet with far lower variability. Its thermal expansion rate (~16 × 10⁻⁶ in/in/°F through the thickness) and repeated‑load stability make it dependable for floors, walls, and roof spans exposed to environmental cycles.

Certified grades such as APA A‑C or EWPAA Structural undergo evaluations for edge stability, fastener holding, and surface hardness to ensure uniform performance. For cost‑sensitive or moisture‑rich projects, CD Structural plywood retains strength superiority to OSB or MDF because of uniform adhesive bonding under controlled pressure and heat during manufacture.

Elevate Your Brand with Custom Wooden Coasters in Bulk

Aesthetic Comparison: Edges and Grain

Plywood shows a layered edge and a thin face veneer, offering uniform aesthetics and modern appeal, while solid wood features continuous grain and natural variation that ages into patina over time.

Grain Continuity and Character

Solid wood has a continuous grain and color pattern throughout the entire thickness, with knots and figure that add unique personality to each piece. Each board carries its own pattern, so even parts cut from the same tree display slight differences in tone and growth-ring spacing. This natural variation creates character and visual depth that remain even after years of finishing and refinishing work.

Plywood shows a natural grain only on the outer face veneer, typically 0.5–0.6 mm thick, which limits how deeply the surface can be sanded or refinished. While this veneer provides an even and predictable appearance, it lacks the depth and natural irregularity seen in solid wood. The engineered layers beneath mainly contribute to structural stability rather than visual interest.

Edges, Layers, and Aging Aesthetics

Furniture‑grade plywood edges reveal alternating plies, often between 5 and 13 layers in a 3/4‑inch panel. These layers can be left exposed and clear‑finished to create a modern striped edge, or covered with edging material for a uniform look. The cross‑laminated build allows clean, crisp reveals that stay consistent with humidity changes, making plywood a preferred option for contemporary designs emphasizing precision and uniformity.

Solid wood edges display uninterrupted grain that can be sanded and refinished multiple times. Over time, the material develops a surface patina as the fibers oxidize and the finish matures. This aging process adds warmth and depth rather than wear. In contrast, plywood’s thin face veneer limits how often it can be resurfaced; aggressive sanding risks exposing the core plies or causing delamination, affecting both texture and durability.

Research Insights

Furniture‑grade plywood generally consists of 5–13 cross‑laminated plies in an 18–19 mm panel. The alternating grain layers are set at 90‑degree angles for dimensional stability. Only the face veneer carries a continuous grain pattern, so exposed edges display alternating grain lines from each ply. This striped edge is often highlighted intentionally in minimalist or Scandinavian‑inspired designs.

Decorative hardwood plywoods use ultra‑thin face veneers of around 0.5–0.6 mm (approx. 1/50–1/42 in). While this thin top layer delivers a premium wood look at lower cost, it constrains refinishing options because sanding through the veneer reveals the contrasting grain direction of the substrate. Solid wood, by contrast, offers enduring refinishability and develops color variation and polished depth across decades of use.

Because plywood cores are manufactured with uniform thickness and density, their surface and edge consistency remains stable. Solid wood is more likely to move with seasonal humidity changes, which can adjust joint lines or cause subtle cupping. Buyers selecting between the two balance the individuality and long‑term surface renewal of solid wood against plywood’s stable geometry and modern, evenly patterned appeal.

Key sources include technical notes from Sinclair Cabinets on veneer‑core aesthetics, Royale Touche on plywood versus solid wood appearance, and Craftsmen Hardwoods on stability and consistency across engineered cores.

Cost Analysis for Makers

Solid wood costs thousands to tens of thousands of yuan per cubic meter with up to 40% waste, while plywood costs several hundred to around a thousand yuan per cubic meter with less than 15% waste, offering more efficiency for makers.

| Material | Approx. Cost (per m³ or per sheet) | Waste / Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Wood (oak, maple, redwood) | Thousands to tens of thousands of yuan per m³ | 30–40% waste from defects and cutting |

| Plywood (veneered or engineered) | Few hundred to ~1,000 yuan per m³ | <15% waste from veneer processing |

| Softwood-core Plywood (pine, fir) | $15–$55 per 4×8 ft sheet (up to $120 for marine-grade) | 5–10% cutting waste, 15–25% lighter for shipping |

Material Cost Drivers and Waste Efficiency

Solid hardwoods such as oak or maple are priced in the thousands to tens of thousands of yuan per cubic meter. Their processing involves cutting around defects and irregular grain, which leads to 30–40% waste. This lost volume significantly increases the effective price per usable piece, especially for furniture-grade boards that demand clean faces and minimal knots.

Plywood, by contrast, relies on veneer peeling and engineered layering that use smaller or lower-grade logs efficiently. This keeps waste below 15%. The production process uses adhesives and pressure to produce uniform sheets that are highly stable. Prices typically start at a few hundred yuan and reach around 1,000 yuan per cubic meter for common grades. The ability to yield more product from the same amount of raw material lowers the cost per unit area.

Softwood-core plywood, built from pine or fir, trims another 15–30% off the cost compared to hardwood-core panels such as eucalyptus or poplar. The lighter weight and consistent density reduce the load on presses and cutters, improving manufacturing throughput in large-scale production lines.

Sheet Pricing, Weight, and Production Implications

Standard 4×8 ft plywood sheets range from roughly $15–$55, with marine-grade or Baltic birch types priced higher between $80–$120. These figures make plywood a predictable material for cost estimation, particularly for cabinet makers and interior paneling shops. A standard 3/4″ sheet of CDX or ACX plywood typically sells for $40–$60, while Baltic birch of similar dimensions can exceed $100 because of its superior veneer count and consistent grain.

Softwood plywood panels are 15–25% lighter than hardwood-core counterparts, which translates directly into lower shipping costs and easier manual handling on the workshop floor. This advantage scales in projects where transportation and labor weigh heavily on total expenses. Plywood cutting waste averages only 5–10%, further optimizing yield for bulk production runs.

Considering the lifecycle economics, plywood offers clear efficiency in volume manufacturing. Its structural stability and resistance to warping cut down on rework and long-term maintenance. Makers producing batches of furniture, cabinetry, or fixtures gain predictable results at lower material costs. Solid wood still holds value for premium applications where natural grain aesthetics or traditional craftsmanship are prioritized, but its higher waste and cost limit feasibility for high-volume output.

Finishing Considerations for Both Materials

Plywood’s layered construction makes finishing easier and more stable, while solid wood needs extra care to handle grain variation and moisture movement during surface coating and protection.

Surface Preparation and Finish Compatibility

Plywood’s cross-laminated veneers create a stable, even surface that accepts paint, veneer, and other coatings consistently. The perpendicular layering of veneers minimizes the chance of splintering along edges and allows finishes to be applied with uniform coverage, reducing the amount of sanding and sealing needed before coating.

Solid wood, on the other hand, requires methodical sanding along the grain direction and careful application of sealers or conditioners. Natural grain variation causes uneven stain absorption, resulting in color differences that need additional surface preparation to correct. This makes solid wood finishes visually richer but also more labor intensive to standardize.

Durability Standards and Environmental Resistance

Hardwood plywood follows ANSI/HPVA–1–2004 standards, which specify uniform hardness, grading, and performance consistency. These standards ensure predictable coating adhesion, structural stability, and dimensional reliability. The specifications define strength and stiffness properties related to veneer type and adhesive bond, enabling durable finishes with minimal warping during temperature or humidity fluctuations.

Marine-grade plywood incorporates waterproof bonding and optional fire-retardant treatments for maximum resistance in wet or high-moisture environments. This prevents delamination and surface blistering that can compromise coatings over time. By contrast, solid wood moves with changes in humidity and often requires resealing or refinishing between seasons to prevent cracking or checking on coated surfaces. Regular upkeep is crucial to maintain its original texture and color integrity under variable environmental exposure.

Comparatively, plywood’s cross-laminated structure enhances resistance to warping and surface deformation, reducing coating stress under environmental load. Variants such as MDF-core or OSB-backed plywood further increase dimensional stability, screw-holding capacity, and flatness, ensuring long-lasting adhesion of finishes. In cost-sensitive construction, this structural predictability translates into lower maintenance cycles and fewer refinishing needs compared to solid wood, which offers natural aesthetic appeal but higher upkeep demands in fluctuating climates.

Suitability for Laser Cutting and Engraving

Plywood generally performs better in laser cutting and engraving than solid wood due to its stable layered structure, consistent thickness, and smooth grain that deliver precise cuts and detailed engravings with minimal warping or burn marks.

Material Behavior in Laser Processing

Birch plywood maintains dimensional stability thanks to its cross-layered design, reducing warping under heat exposure. The uniform grain pattern ensures a steady absorption of laser energy, making it reliable for precision applications such as model cutting or architectural mockups.

Solid wood can expand or char unevenly, leading to inconsistent kerf width and unpredictable edge burn. Variations in fiber density across the grain often cause irregular beam penetration, creating surface blemishes and imperfect joints when assembling laser-cut parts.

Laser-grade plywood is preferred for its uniform thickness, allowing repeatable precision cuts across sheets. It minimizes dimensional errors across multiple passes, an important factor for designers creating interlocking or friction-fit components where tolerance must be consistent.

Laser Settings and Performance Data

CO2 lasers from 60–100W can cut plywood up to 15–20mm thick at around 55% power and 45mm/s for 3mm sheets, while diode lasers handle lighter jobs under 10W. The high-efficiency beam of CO2 lasers vaporizes adhesive and cellulose layers evenly, resulting in cleaner edges compared to diode output.

Engraving power typically ranges between 10–20% at 400–600 mm/s speed on plywood, with deeper marks achieved at slower speeds between 3–20 mm/s. Fine raster engraving benefits from lower power settings that preserve tonal gradients without burning through the top veneer.

Air assist and multiple lower-power passes reduce edge charring by clearing residue while minimizing thermal buildup. Adequate ventilation removes smoke and gases released from glues within the plywood core, maintaining cut clarity and operator safety in enclosed laser environments.

Kerf tolerance around 3.175mm (1/8 inch) ensures tight fits for interlocking designs. Using calibrated test cuts to measure kerf before project runs improves accuracy for box joints, inserts, and other precision assembly models made from plywood sheets.

Research Summary

Birch plywood remains the industry standard for laser applications because of its layered design, stable structure, and fine grain. These characteristics keep dimensions consistent across large surfaces and minimize energy loss through variable density zones. The most effective setup utilizes CO2 lasers between 60–100W, cutting material thickness up to 20mm with accurate kerf widths and clean separation of bonded layers.

Diode lasers, although suitable for smaller-scale or engraving work, offer limited penetration at comparable feed rates. Processing parameters such as 55% power at 45mm/s for 3mm plywood and 10–20% power for engraving yield reliable, repeatable quality. Safety systems including exhaust ventilation and protective eyewear are mandatory due to vaporized adhesives and smoke created during operation.

There are no standardized ASTM or ISO classifications defining plywood’s laser suitability. Parameters originate primarily from equipment manufacturer guidelines, such as those from RECI W-series CO2 laser systems. Compared to solid wood, plywood’s layered makeup reduces deformation in mechanical joints, particularly in multi-pass operations where solid wood’s uneven expansion can lead to failure or aesthetic inconsistency.

Making the Choice for Your Project

Choosing between plywood and solid wood depends on what your project values most. Plywood brings stability and sheet coverage, while solid wood offers strength, character, and premium durability in visible or high-stress areas.

Balancing Stability, Aesthetics, and Budget

Plywood’s cross-laminated veneer layers resist expansion and contraction caused by humidity shifts, providing reliable flatness for cabinetry and panel assemblies. This structure helps maintain consistent dimensions even in environments with fluctuating moisture levels, making plywood a preferred option for panels or carcasses that need to stay true and aligned.

Solid wood delivers natural grain character and higher span strength, but it moves more with seasonal humidity, needing joinery or design allowances to prevent warping. Frame-and-panel construction, floating tops, or quartersawn stock help offset these changes while preserving the distinct look of real wood.

Projects often combine the two: plywood for structural shells and solid wood for trim, face frames, and touch surfaces. This hybrid method keeps costs manageable while taking advantage of each material’s best properties—stability from plywood and beauty from solid wood.

Evaluating Strength, Moisture Resistance, and Material Selection

Standard plywood sheet size is 4×8 ft with thicknesses between about 3/16 in and 3/4 in, giving flexible coverage for furniture and built‑ins. These uniform panels make it easy to cover large surfaces efficiently while maintaining dimensional accuracy.

Marine‑grade plywood offers top moisture resistance, while MR and structural plywood suit lower‑exposure interiors. Builders can choose the right grade depending on humidity exposure, balancing performance with cost efficiency.

A 1×8 solid pine board generally deflects less across a span than equal‑thickness plywood, making it ideal for beams or rails. This higher stiffness per unit thickness supports applications where bending resistance is critical.

Durable hardwoods like teak or Sheesham outlast softwoods such as mango or pine for high‑wear furniture. Their dense grain and natural oils enhance lifespan and resistance to wear in premium installations.

Research Summary

From an engineering standpoint, the core decision in choosing material depends on how much you value dimensional stability versus span strength and appearance. Plywood, made from veneers bonded with the grain at 90°, delivers consistent strength and reduced warping. It’s usually sold in 4×8 ft sheets, 3/16 in to 3/4 in thick, making it practical for cabinets, built‑ins, and panels that must remain flat.

Solid wood, on the other hand, gives higher span strength and structural performance per thickness. Because it reacts to moisture changes, careful joinery and design strategies—like floating panels—help manage expansion and contraction. Hardwoods such as teak and Sheesham provide long service life in areas where durability matters most, while softwoods are suited to low‑stress or decorative elements.

For balanced projects, a cost-effective strategy is using plywood for stable, structural shells and solid wood for visible load-bearing components. This approach delivers strength, aesthetics, and cost control without compromising structural integrity or long-term performance.

Final Thoughts

Plywood has earned its place alongside solid wood as a dependable material for both makers and designers. Its layered construction provides reliable strength, consistent stability, and cost benefits that support large-scale production without sacrificing quality. While solid wood maintains its edge in authenticity and long-term refinishing potential, plywood offers a smart balance of performance and efficiency that meets most modern requirements for furniture, cabinetry, and crafted décor.

When deciding between the two, think about how the piece will be used and what qualities matter most—appearance, strength, or environmental resistance. Solid wood brings natural beauty and tactile richness, while plywood offers precision, dimensional certainty, and economy of scale. Many of the best designs use both, proving that plywood isn’t a lesser substitute but a thoughtfully engineered material fit for professional and creative work alike.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is plywood water resistant?

Standard plywood tolerates only mild humidity because it uses urea formaldehyde glue. Water‑resistant BWR grade can handle about eight hours of boiling water, while BWP (marine/710 grade) endures more than seventy‑two hours without delamination under ISI:710 standards.

How do you hide the plywood layers on the edge?

To conceal the layered edge, apply edge banding or a slightly wider solid‑wood edge. Veneer, PVC, or ABS banding is usually 0.5–3.0 mm thick, while solid‑wood edging around 9.5 mm is used for tabletops or other high‑impact areas, trimmed and sanded flush for a clean look.

Is solid wood always better?

Not necessarily. Plywood often matches or exceeds solid wood in stability, ease of work, and cost efficiency. Solid wood offers stronger span performance, but plywood provides consistent strength within its layered structure and comes in convenient sheet sizes such as 4′ × 8′ and thicknesses from 3/16″ to 3/4″.

Can you laser engrave plywood?

Yes. Plywood can be laser‑engraved using diode or CO₂ systems. A minimum of about 10 W diode (20 W ideal) or 40 W CO₂ power works for engraving speeds roughly between 3 mm/s and 400 mm/s, typically engraving the top veneer layer in thicknesses from about 3 mm to 18 mm.

Which is better for painting?

Paint‑grade plywood such as MDO plywood (meeting PS 1‑09 standards) offers a flatter, more uniform surface than solid wood. It resists movement from humidity changes, accepts paint smoothly, and avoids surface defects common in lower‑grade solid woods.